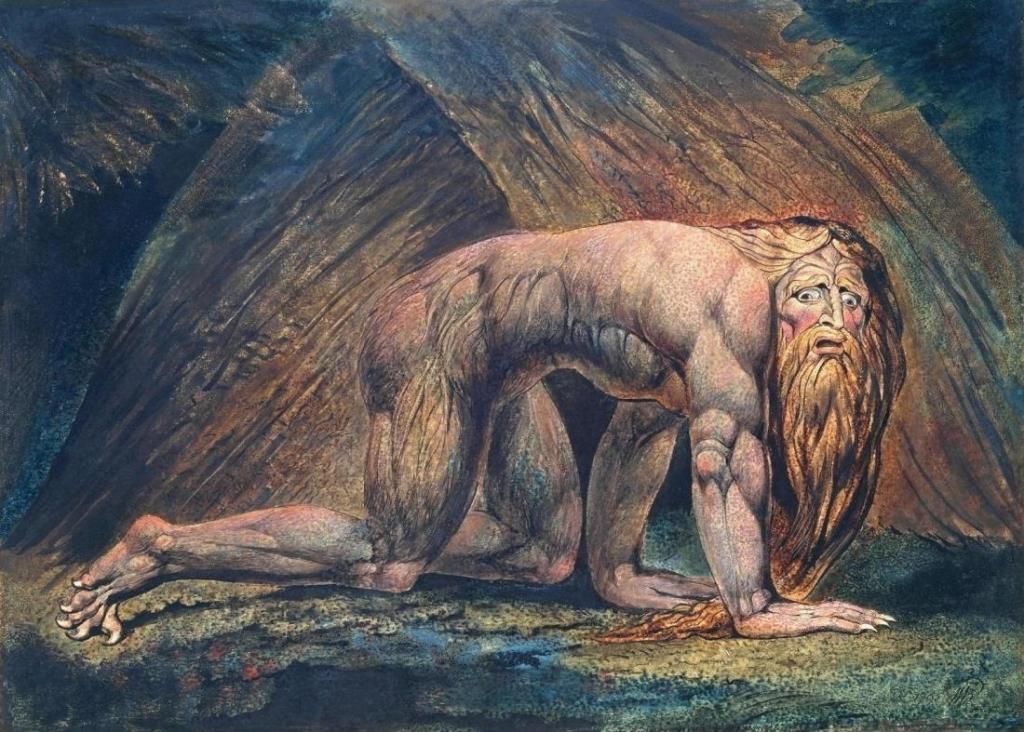

When King Nebuchadnezzar’s mind was warped and addled by God as punishment for his hubris, he spent seven lowly years as any unclean biblical animal. He ate sallow, sickly grass, his beard features grew bestial and for seven long years the most decorated, long-lasting king of Babylon reverted to a state of beasthood.

This metamorphosis, of course, is not an uncommon occurrence throughout mythology, literature and media. Across continents and across culture, the trend of man either embracing or attempting to conceal his – literal – bestial nature is persistent. This traces back to at least to Proto-Indo-Europeans, to the Iron Age of Europe, to the Scythian Neuri’s metamorphosis, to Lycaon, and is ingrained in the role of the wolf in Germanic tribal belief.

Of course, the most prominent manifestation of the metamorphosis in modern times is the phenomenon of clinical lycanthropy. Broadly defined as the delusion of having the ability to transmogrify into a werewolf, the phenomenon is, as expected, not given much attention when the delusion is purely literal. Often linked to conditions like rabies, or associated with cases of feral children. Naturally, the psychological implications have attracted more contemporary investigations, rather than the cultural or literal implications. This hasn’t always been the case, however.

This is most prominently written about in Robert Eisler’s Man Into Wolf; An Anthropological Interpretation Of Sadism, Masochism and Lycanthropy. Eisler claimed that the historical precedent for the werewolf is born from food shortages during the ice age. As a result of this, a subset of men imitated the actions of wolves to hunt more efficiently, distancing themselves behaviourally from the pre-lycanthropic hunter gatherer, as it were. Their embrace of the lycanthropic, Eisler claims, forever changed

Eisler points to this bestial embrace as the basis for man’s sadism. That before this functional lycanthropy, man existed in a state of blissful whimsy, of sexual liberation, of relative peace. The mental metamorphosis of man forever split our nature in two – implying that a propensity for violence, cruelty and sadism is a result of a sort of genetic fall from grace, of some ancestral deviation from the prescribed natural order. For Eisler, when man began to adopt these bestial traits and behaviours was the moment we bit the apple of Eden.

Eisler’s belief in this suppressed ferality isn’t unfamiliar to us within a fictional lens. Even removed from the more obviously analogous works of fiction depicting werewolves, there is no shortage of fiction depicting man struggling to suppress primal urges and violent tendencies, resisting the urge to succumb to what Eisler considered a genetic predestination.

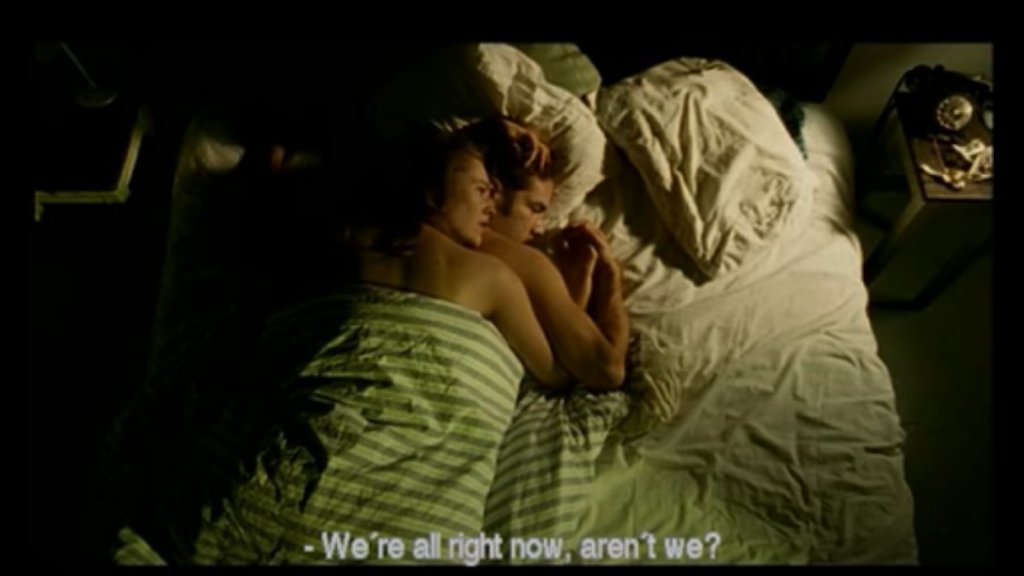

This change is present throughout Steve Ericsson’s 2002 film Lyckantropen. The film, who’s broader exposure is due in part to the Ulver score which accompanies it, is a short-on-words short film bursting with paranoia and bestial impulses. Smeared with sickly green lighting that tints each shot. Jaggedly cut Dutch angles. A visceral sense of dampness permeates every inch of the film.

Throughout the runtime, a seemingly regular househusband fights off his bestial urges. Throughout the film a point is made of the cyclical, routine nature of the man’s actions. He checks himself every morning obsessively, the film bookends itself with the married couple in bed asking “We’re alright now, aren’t we?”. We reach the climax of the film where the husband kills a mirror of himself, a doppelganger acting as the unrestrained, animal instinct he’s attempting to repress. The film ends with the aforementioned question from the couple in bed, suggesting that this a regular occurrence.

Ulver – whose moniker translated from Norwegian is, suitably, Wolves – scoring the film is hardly accidental, either. A group then-caught between the esoteric and ferocious trappings of their early blend of Black Metal and Neofolk, Ulver balanced this knife-edge of a tonal melting pot with care. Following the release of their third record, Nattens madrigal: Aatte hymne til ulven i manden, Ulver made the leap from Black Metal to electronically driven music, only occasionally showing the spirit – if not the letter – of their early material since. Much like the protagonist of Lyckantropen, Ulver’s bestial roots can be hidden below the surface – but continue to rear its head.

Perhaps a more fatalistic example is Lovecraft’s The Shadow Over Innsmouth, wherein the narrator’s direct relation to Obed Marsh – and by extension, his relation to the deep ones – has predestined him for a bestial existence. Unlike Lyckantropen, however, The Shadow Over Innsmouth‘s narrator does not seem to possess some innate bestial trait at first. In fact, his bestial nature is only made apparent to us when he ultimately embraces his inhuman bent. While published before Man Into Wolf, the comparison is still useful in this instance.

Two men, two decisions, both unintentionally outlined Eisler in this tradition of functional lycanthropy. Thoughts to remember after Hallowe’en.

Initially posted on the old website, November 8th, 2020.

Leave a comment