A decade removed from the peak-dominance that Club music – here used as a loose term for the club-centric and club-focused merger of EDM and Pop sensibilities with the aesthetic and spirit of 2000s R&B – held on the charts, and popular music has largely replaced the earnest, if thick, grinning death head of rave culture it represented.

Pop music’s progression since then has been contextual as well as tonal. The nightclub-centric basis of those who ruled the roost of the late 2000s Pop environment gave way to a Pop landscape more directly influenced by the massive increase in diagnosed mental illness, particularly suicidal ideation, and particularly again in young people.

Pop music took on a form that was significantly more sparse in its production, more melancholic in its vocal delivery – though crucially, not significantly different in its consumption. Artists who’ve managed to score hits in both the 2000s and 2010s often display this disparity in its highest clarity. A musician such as Mike Posner, who can score two massive club hits in the form of the Electro-House tinged Cooler Than Me – with its humble-braggadocia and semi-slurred delivery implying the Flo-Rida soundtracked, drunk club setting of the late 2000s – and the Tropical House influenced remix of I Took A Pill In Ibiza – with its sly appropriation of Mumble Rap trappings and faux-melancholic delivery – shows the massive, yet rarely acknowledged, gap in tone, context and influence.

It’s a time that saw the transition from popular music’s drug of choice – from the unspecified alcohol presented in an almost childlike naivety in popular Club music – to opiates. There was a near-jovial nature to the way alcohol and drugs were depicted in the Club landscape, especially when compared to the way that Pop music a decade later would wear the gradual cultural acknowledgement of the opioid crisis on its sleeve. Something like Far East Movement’s Pop Rap smash hit Like A G6, or Asher Roth’s wanker-slacker anthem I Love College deal with drugs and alcohol in a way that, if released today, would be regarded as totally alien and a little tasteless.

However, as distanced as popular music has become from the aesthetic trappings of 2000s Club music, it has remained functionally identical in its consumption and enjoyment by its audience. A decades difference, but play it on the dance floor and they’ll still get the same results.

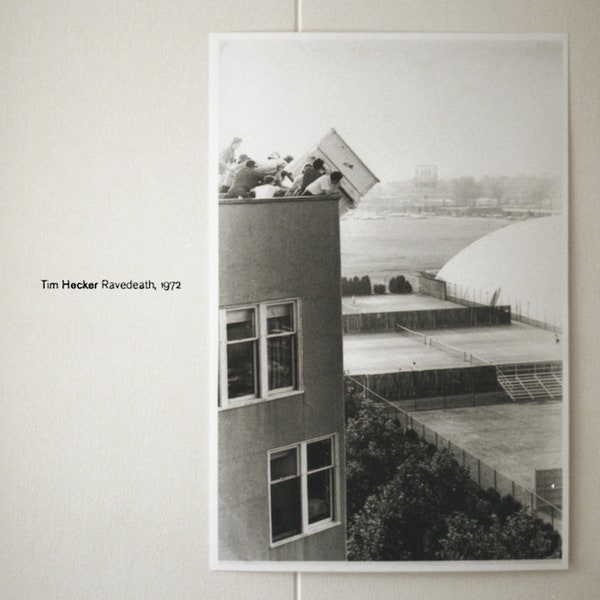

In 2011, just as the transition between the Club music of the 2000s and the Pop music of the 2010s was beginning to take hold, Tim Hecker released one of his more celebrated releases – Ravedeath, 1972. Recorded with Ben Frost, Ravedeath, 1972 is a freezing cold collection of organ-driven Electronic Music. It’s title is the most pertinent detail here. More specifically, the word Ravedeath. A word that came to Hecker during a rave in 2010, a word that was as ambiguous to Hecker as it was to the listener.

Taken in conjuction with the music found on the record – live organs corroded with digital distortion, an aural rumination on decay – Ravedeath seems a perfect term for the experience of the contemporary club, of the necromantic-raves hosted as melancholic shells of what came before. Of the clinically depressed no longer finding emotional solice in the music that once moved them – numbed memories of anxiety permeating the undulations of the club.

It’s something that an increasing amount of people can relate to. As mentioned earlier, a combination of both mass suicidal ideation and widespread opioid abuse has changed the landscape of the cultural underground. The downstream trickle of this has superficially permeated pop music and its aesthetics, but I don’t think we’ve seen a properly massive pop star integrate Ravedeath in a way that wasn’t surface-level.

Alice Glass is a figure who’s surprisingly unsung despite the breadth of her influence. Her status as the centrepiece of Crystal Castles during the height of their relevance awarded her the rare (mis)fortune of being both lauded by the popular music press and the Internet musicsphere alike. The stacatto, bitcrushed bitpop of their now-seminal debut beget so much in the following years.

The burgeoning microgenres that dominated the internet during the dying days of the music-blogosphere’s period of relevance, Witch House, Chillwave, et al – of which Glass was a key contributor to – is directly upstream from future microgenres that sprouted in popularity in the following decade – Hyperpop, Bubblegum Bass, et al.

It’s a record that didn’t predict anything, it didn’t create anything totally new, but like so much great Pop music – particularly crossover success stories – it integrated and appropriated its influences with taste and respect, making an accessible record without dulling much of its underground edge. It retained the danceability of then-contemporary Pop, but with a harsher, spiky exterior.

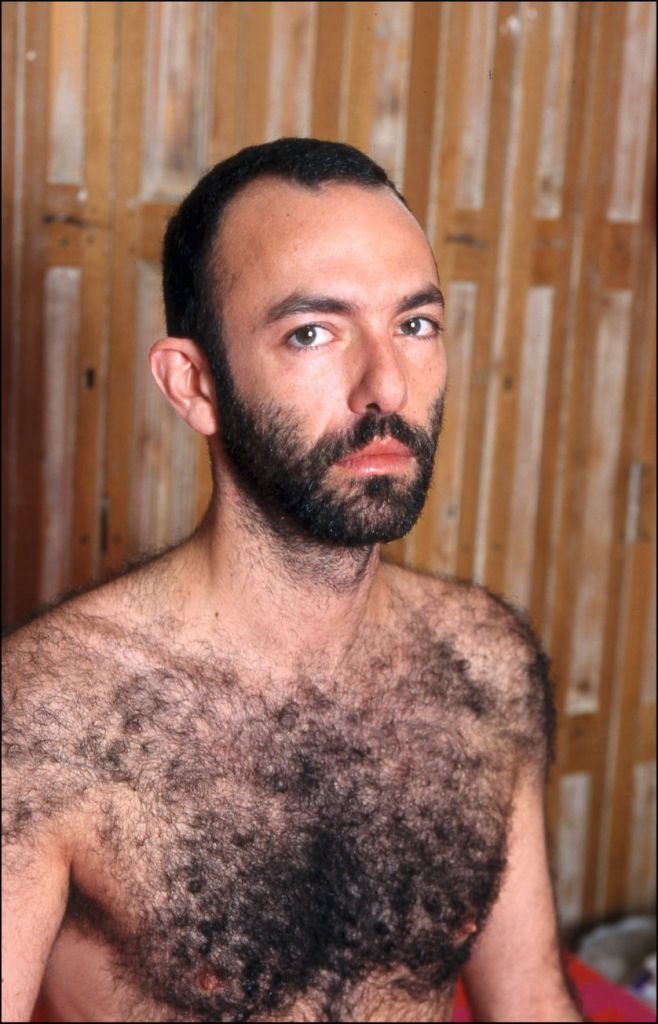

Guillaume Dustan, attempting to conquer the death drive and AIDS through sex and techno rave dancing

However, in the latest release by Alice Glass, the 2022 LP Prey / IV, the distorted and stacatto emotional output found on her earlier music are significantly numbed, like a field of suppression is enveloping the whole record.

The record is permeated by this coldness and vacancy, even when Alice’s vocals are sharp and screaming, even when the music becomes more traditionally beat driven, developing the Witch House and Bitpop of her earlier output into a more flagrant Electro Industrial flavour, there remains this dichotomy.

Beat driven music – by all accounts Electronic Dance Music – but written in an almost confessional manner. The EDM DNA flowing through what Alice Glass plays often attempts to create space for interpretation. Lyrics are often sampled, disjointed, pitchshifted beyond recognition. The listener can engage with the music on several levels, and the freedom of interpretation of image and meaning is a primary reason why. Alice Glass, coming off the back of traumatic life events from her involvement in Crystal Castles, chooses not to obfuscate her experiences as is often the case in dance music. Distress is worn on the sleeve. The music is riddled with anxiety, unable to be separated from its original context of abuse.

The whole of Prey / IV sounds sounds like unsuccessfully trying to forget trauma in a rave – stomping feet and flowing limbs desperate to replace burnt synapses and searing memories – only for visions of the past to creep in through the sparse lyrics, the spaces in the drum syncopation, the searing synth tones. This seems like the perfect pairing for Ravedeath.

The closest literary equivalent of what I’m calling Ravedeath is French Autofiction auteur Guillaume Dustan, particular the collection The Works Of Guillaume Dustan, Volume 1 – a compilation of his novels In My Room, I’m Going Out Tonight and Stronger Than Me.

Dustan’s novels are autofictional accounts of the narrator’s increasingly numbed existence interspersed with the scenes of gay Parisian nightlife in the 1990s. The narrator, diagnosed as HIV positive, invariably spends most of each book living with an understated but omnipresent ticking-timebomb.

The narrator documents a numbed nightlife, cruising for fucks to help him either forget or conquer the death-drive and his reduced life expectancy – he gives himself five years at one point. Every decision is second guessed, from evaluations of the attractiveness of other cruisers, to the prospect of taking someone home, to taking poppers, to using the minitel, every decision teems with anxiety due to the deliberately excessive description of the narrators mental processing.

The narrators – in having the almost cursed knowledge of his life expectancy – lives with the ghost of his lost future at all times. This begins to penetrate even his escapism. The Techno of his nightlife dulls and makes the outlines of his anxieties weaker, less permeable, but they never leave, never truly is he in a state of contentment devoid of anxiety. Uniquely, Dustan positions the narrator himself as the figure of Hauntology throughout his novels, and not necessarily the music, art and culture he moves through. Living in numbed melancholy to the ghosts of his future – his ghost. Like Alice Glass, the narrator does not obfuscate his words, doesn’t cloak them in metaphor, his distress and anxiety is worn on his sleeve.

Ravedeath is a numb present, and a lost future.

Leave a comment