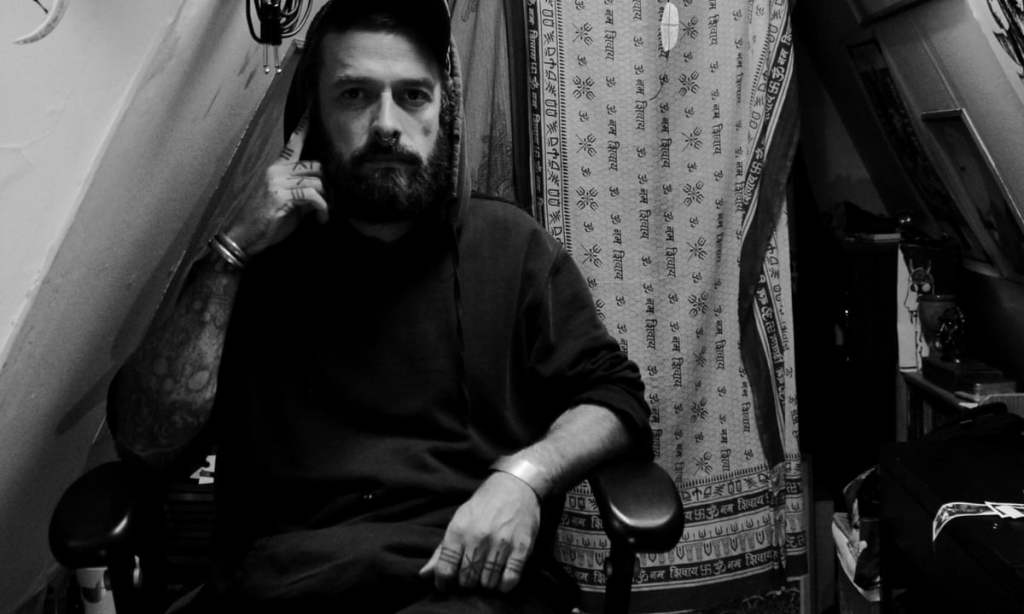

Iain from One Leg One Eye and Lankum was kind enough to chat with me about urban folklore, Irish landscapes, black metal, pre-Lankum records and more.

Was listening to the Don Seantalamh a Chuid Féin Sodb demo and thought it was class, a lot more bass-heavy than a lot of similar black metal demos of that ilk. What was your experiences in that project and does black metal still influence your music in any way?

Sodb formed around 2011 from the ashes of an earlier BM project called Dordaid Dam. I was in the middle of a big BM phase at the time and also researching a Master’s Thesis in Irish Folklore. I think nearly every musical project I’ve been involved in ha been influenced by Irish mythology and folklore to some degree, but with Sodb I went all out and wrote lyrics as Gaeilge as well. The concept of the band was based on negative manifestations of the sovereignty goddess as found in descriptions from manuscripts in the Old Irish language. I loved the project and had a lot of fun playing gigs with them. The bass player, Irene Siragusa, is an amazing musician and went on to play with the band Abaddon Incarnate. I would say that Black Metal as a genre continues to inform my music yes, particularly with One Leg One Eye where I think it is most obvious.

You’ve spoken about finding inspiration from an old factory in Howth where your father worked when you were small, and more recently performing and recording inside of it, could you talk a bit about that and its significance to you?

Yeah, it was a factory where my father worked in the 80s when it was called Parsons. Me and my brother used to go in with him on Sundays and wander around the factory floor trying to keep ourselves amused. I started to spend time there during lock down when I found that I could access it through a broken toilet window. I used to sit in the cockpit of the big crane and play the sruti box and sing to myself, just enjoying the reverberations and echoes of the sound as it bounced around the massive room. I made some recordings in there and they were the first iterations of what became One Leg One Eye.

The landscape around Baldoyle and Howth where I grew up made such an impact on me and I still dream of it and the way it was in my childhood all the time. Before lockdown I ended up moving back to my parent’s house and was going through a lot of inner child work so interacting with the landscape in various different ways seemed very important to me at the time.

As an extension of that, so much of Ireland is dotted with disused and abandoned places – boarded-up accommodation, abandoned sites and overgrown paths. Even though your music is indebted to folk traditions there’s occasionally that feeling of urban desolation in its thick, resonant drones – I suppose I’m wondering to what extent you’re influenced by the landscape of Ireland? Either its cities or its country.

I think it’s important to recognise that urban centres have as much folklore and traditions attached to them as rural areas do. Dublin city has its very own song tradition and this is one aspect that I’ve been very interested in over the years. I think it’s important to let your environment seep into the music and art that you make and it’s to be heard in One Leg One Eye in the soundscapes and field recordings that I made for the album. Baldoyle to me is a very liminal place. When I was growing up there it seemed like it was on the very edge of Dublin, with endless fields and hinterland stretching out behind my parent’s house for as far as I could explore. This liminality and the strange magic that it can engender is something that I’m interesting in digging into and also finds its way into the music.

How did you come about doing the score to All You Need Is Death? And was it difficult writing for film as opposed to writing for a regular LP?

I agreed to compose the soundtrack to All You Need Is Death after meeting with the director Paul Duane. I had never done anything like that before, but I was lucky in that Paul was so easy to work with. I also had a lot of time, being involved in the film from the very first drafts of the script. To be honest, I loved the whole process. I found that because so many of the parameters were dictated by the scenes themselves – how long a piece should be, what mood it should have, what the tempo should be etc. – a lot of the humming and hawing and second guessing was taken out of the equation for me and I could just go straight ahead and write the music, so it all came to me quite easily.

…And Take The Black Worm With Me sounds a lot more intimate and singular in scope than other records you’ve been on, was it easier to make something solo or was it a challenge being totally independent like that?

There might have been one or two challenges, but overall I found working by myself much easier than working with a band! I want into it with the idea that I shouldn’t worry about the end result and to just throw myself into the creative process and enjoy it as much as I could and as a result I’d say I had one the best musical experiences I’ve ever! It’s definitely changed how I view making music.

It’s been over 20 years since Where Did We Go Wrong, how do you feel about the record now? It’s such a unique album in your discography but still retains that DIY ethos that’s present in your newer stuff.

Where Did We Go Wrong? is probably the most DIY album I’ve ever been involved in. It was recorded in a friends bedroom and me and my brother made CD copies and photocopied all the covers ourselves. We were delighted to hear that after our tour of Mexico in 2006 that all the punks down there were bootlegging the album and our t-shirts as it meant that we didn’t have to do it. It wasn’t until a good few years later that Georgetown Records put out the vinyl version. It’s a pretty hilarious album for me. Very cringey, but I’m happy that it exists in the world and is a document to a pretty crazy period in my life!

How do you feel about the state of Irish music at the moment? As a listener it seems like there’s a lot of active great independent music coming out right now.

I think there is really amazing Irish music being made now across all genres and it’s so good to see. Being in a band is not easy and at times seems like more of a vocation than anything else, but I think there will always be people who want to do nothing else in life.

How has the transition to live performances been as One Leg One Eye? Does the material translate easily to a live setting or did it require any re-working?

Well after the album came out I got quite a few offers and turned them all down as I was adamant that I never wanted to play live. Eventually an offer came in for CTM festival and I had a few months relatively free beforehand so I said I’d give it a shot to see if it would work. Me and my partner in crime George Brennan put in a lot of work for that first show, and Lukas Feigelfeld joined us on visuals. We really enjoyed it and decided to keep it going as a live project. As I write we’re in Birmingham about to play at Supersonic, which is probably my favourite UK festival and there’s already offers in for some amazing gigs next year so I think I made the right decision.

What are your biggest non-musical influences right now?

Sacred sites in the Irish landscape, bog bodies, the Mythical Ireland monograph series, micro dosing, Horror films, the Arkham Horror Living Card Game and Magic the Gathering.

What’s your plans for the rest of 2024 and beyond?

I’ve got quite a few recorded projects that I’m hoping to finish up and I’m also working on some new One Leg One Eye material. That and lots and lots of gigs!

One Leg One Eye’s debut record is out now on Nyahh Records.

Leave a comment